Satellites Reveal the Extent of Flooding in Central Asia

In April, severe floods swept across Central Asia, particularly in Kazakhstan and Russia, the aggressor country. The flooding of the Ural, Tobol, and Ishim rivers is estimated to be the worst in the region in the last 80 years. In this article, Elzė Buslavičiūtė and Dr Laurynas Jukna, geographers at the Institute of Geosciences of Vilnius University, answer some questions on how satellites monitor these floods, their extent, and the potential causes.

In April, severe floods swept across Central Asia, particularly in Kazakhstan and Russia, the aggressor country. The flooding of the Ural, Tobol, and Ishim rivers is estimated to be the worst in the region in the last 80 years. In this article, Elzė Buslavičiūtė and Dr Laurynas Jukna, geographers at the Institute of Geosciences of Vilnius University, answer some questions on how satellites monitor these floods, their extent, and the potential causes.

Kazakhstan suffers the worst flooding in 80 years

The Orsk Dam collapsed on 5 April as a result of unusually high temperatures recorded in the region in spring 2024 and the rapid melting of snow in the Ural Mountains. This raised the water level in the Ural River by almost 10 metres, led to the evacuation of thousands of people, and caused millions in damages as well as the shutdown of the Orsk Oil Refinery.

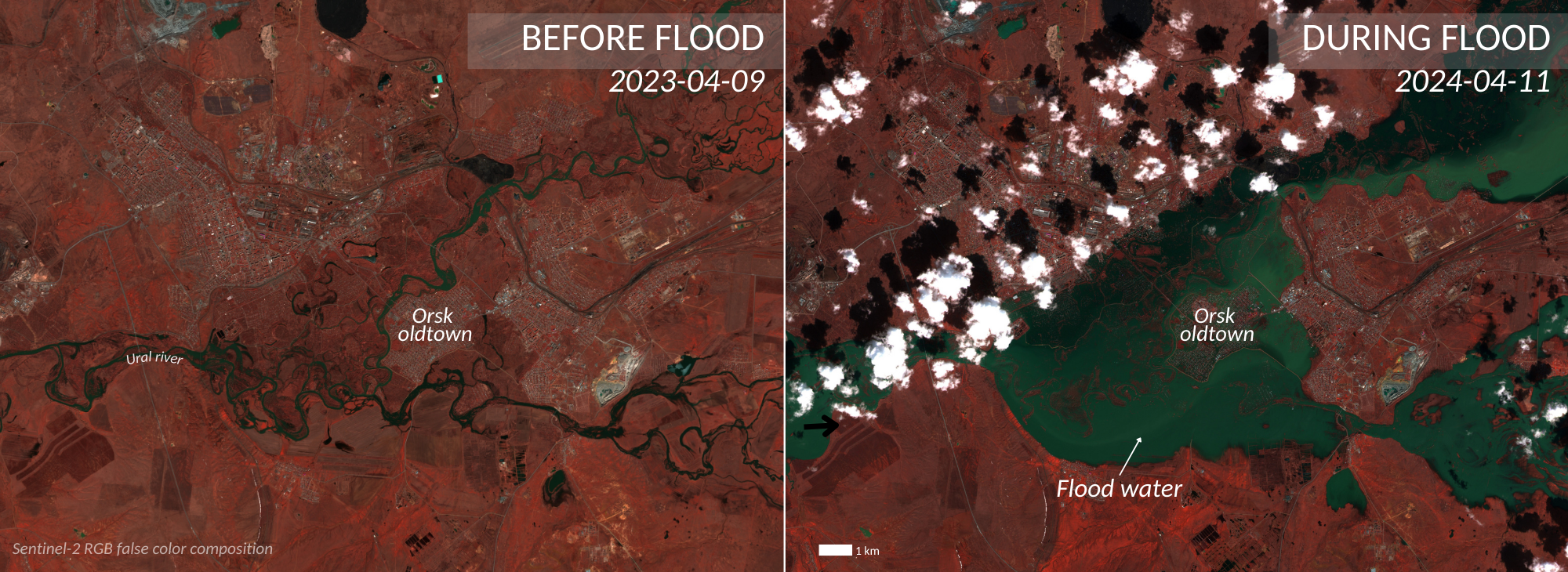

At least half of all floods in the region are caused by rapidly melting snow, around a third – by heavy rainfall, and approximately 15 per cent – by ice jams in rivers. The images captured by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellite over Orsk on 11 April indicate that the Ural River has overrun its banks in the old town of Orsk. The images, showing urban areas and vegetation in pink and water in green, reveal the immense scale of the flooding.

Similar disasters in the territory of the aggressor Russia are becoming a troubling trend

As Russia continues its unprovoked war against Ukraine and the Ukrainian population for the third year running, the bulk of its budget (including infrastructure spending) is diverted to military needs. Not surprisingly, similar disasters have become more frequent in recent years, with increasingly more heating and plumbing breakdowns in many Russian cities during this winter.

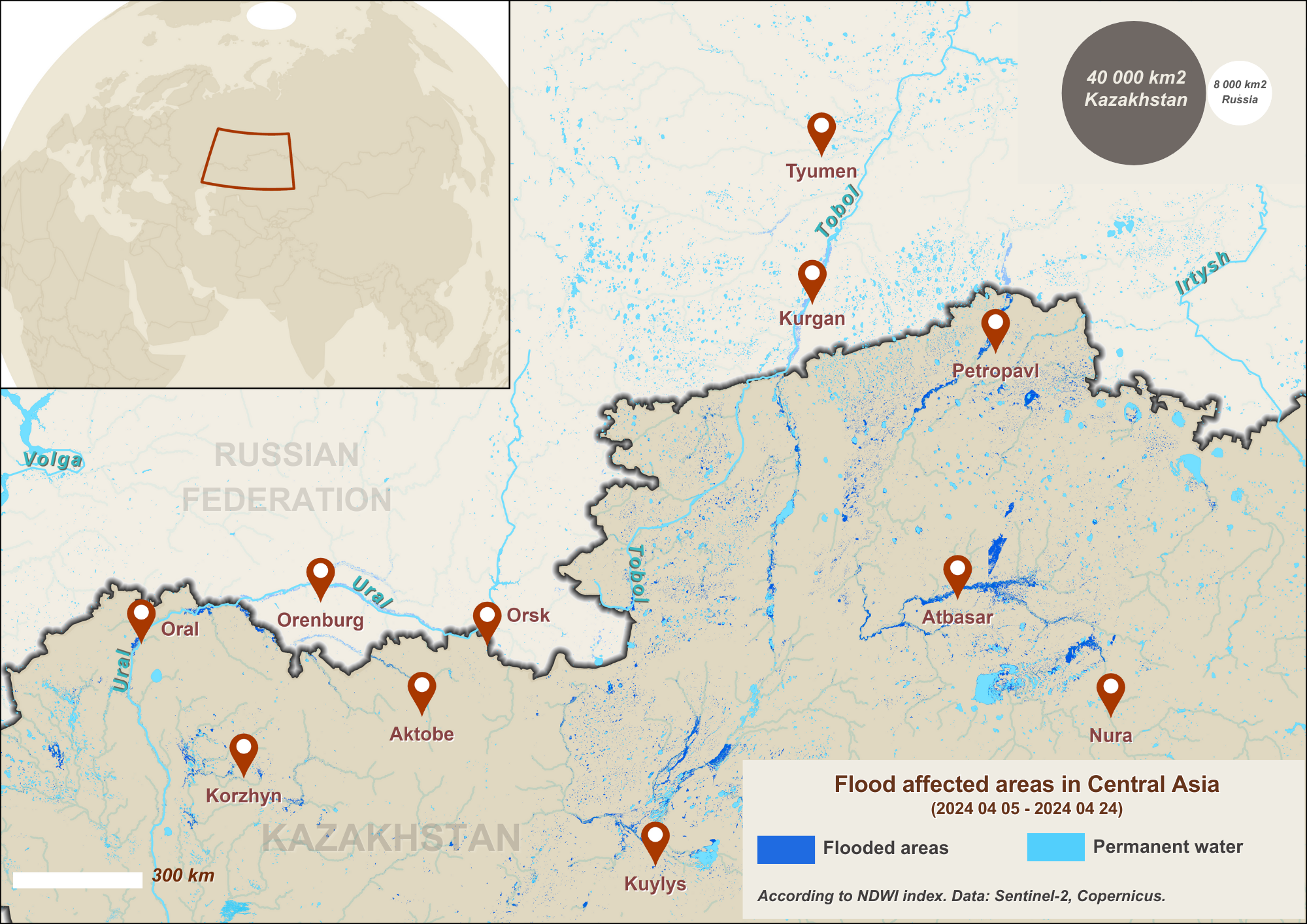

Shortly afterwards, the flooding also reached other cities along the Ural River, including Orenburg, with a population of over 550,000. The Ural River, which flows through Orsk into Kazakhstan and empties into the Caspian Sea, is only one of several transboundary rivers that have seen spring floods. For example, on 17 April, the Kurgan authorities reported that the water level of the Tobol, a tributary of the Irtysh River, in some areas had risen up to 11 metres.

According to the Ministry for Emergency Situations of the Republic of Kazakhstan, nearly 117,000 people have been evacuated nationwide due to the floods. The Sentinel-2 satellite images show the Ishim River spilling over residential buildings in Petropavl, Kazakhstan. The flooding in the country is estimated to be the worst in the last 80 years.

Satellites help see the Earth in new colours

Looking at these satellite images more closely, we can see that the Earth’s surface seems somewhat unusual. This is because it is known as ‘false-colour imagery’. The human eye can see only a fragment of the electromagnetic spectrum, appropriately called the visible spectrum. Remote sensing instruments on satellites have electromagnetic spectrum sensors that measure light beyond our visible spectrum, such as infrared radiation. To imagine what seeing in infrared looks like, we have to find a way to represent the intensity of the radiation in the colours we know.

True-colour imagery was designed to display the Earth in colours that we can see with our own eyes, i.e. a combination of red, green, and blue (RGB) light intensity. In contrast, false-colour composite imagery, as in the case of Petropavl’s flood, displays the near-infrared (NIR) portion of the spectrum using red light, the red band using green light, and the green band using blue light. That is why water, which absorbs infrared light very quickly, appears black and green, while vegetation, which reflects infrared light, appears red.

There is a wide range of remote sensing techniques for monitoring waterlogged areas. If a satellite sensor detects low NIR reflectance values, this may point to detected water surfaces. Based on this and other absorption properties, various indices have been developed in the field of optical satellite studies to help distinguish water bodies and submerged areas.

One of them – the Normalised Difference Water Index (NDWI) – can distinguish between water bodies and soil or vegetation using a combination of visible green and near-infrared wavelengths. This index shows that at least 50,000 square kilometres of territory were flooded in north-western Kazakhstan and south-western Russia between 5 and 24 April. For comparison, the area of the Republic of Lithuania is 65,300 square kilometres.