Melting Glaciers are Shifting National Borders

In Europe and around the globe, melting glaciers are transforming both landscapes and national borders. In this article, Elzė Buslavičiūtė and Dr Laurynas Jukna, researchers at the Institute of Geosciences of Vilnius University, discuss space-based observations of this phenomenon.

Europe’s glaciers and their importance

When we think of glaciers, vast ice sheets in polar regions often come to mind, such as those in Antarctica or Greenland. However, there are many more glaciers in the world, and they are far more diverse. Globally, there are currently more than 200,000 glaciers that do not fall into the category of ice sheets (continental glaciers greater than 50,000 km²).

These include glacial valleys, hanging glaciers, mountain glaciers, ice caps, etc., which are under 50,000 km² and often concentrated in mountainous regions. Such glaciers are also common in Europe, particularly in Iceland, the Scandinavian Peninsula, Svalbard, the Pyrenees, and the European Alps.

Glaciers are massive ice bodies that move under the force of gravity. They form where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation. Over time, snow compacts into firn – partially compacted granular snow – and, eventually, transforms into solid glacier ice.

Roughly 20,000–22,000 years ago, glaciers (or, to be more precise, an ice sheet that shifted from Scandinavia) shaped present-day European terrain, leaving distinct marks on the landscape that still remain visible today. In modern times, glaciers continue to play a critical role: they store freshwater, sustain Europe’s rivers and lakes, and regulate both water runoff and air temperatures.

Monitoring Alpine glacier melt from space

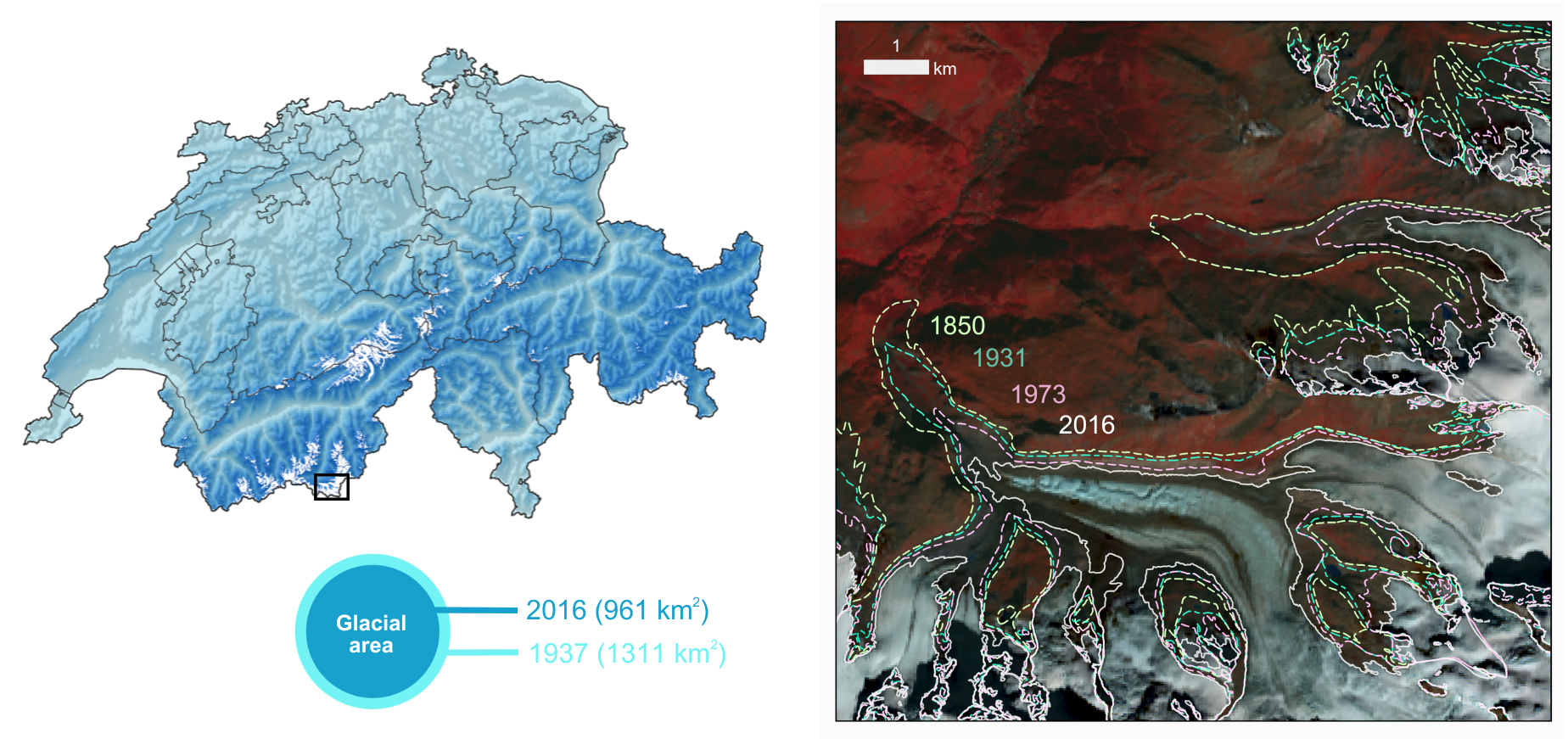

While glaciers in the Alps have been retreating since the end of the Ice Age, the pace of their melting has accelerated in recent decades due to human-induced global warming. According to the long-term observations by Glacier Monitoring in Switzerland (GLAMOS), the area of glaciers in the Swiss Alps decreased from 1,311 km² in 1973 to 961 km² in 2016.

This represents a loss of almost 350 km² of glacial area in under half a century. Such large-scale monitoring is based on archival aerial and satellite imagery.

Glacier melting from 1850 to 2016 in southwestern Switzerland based on GLAMOS aerial and satellite observations. On the right is a false-colour Landsat 8 satellite image from 2 October 2016, with lines indicating the distribution of glaciers during different periods.

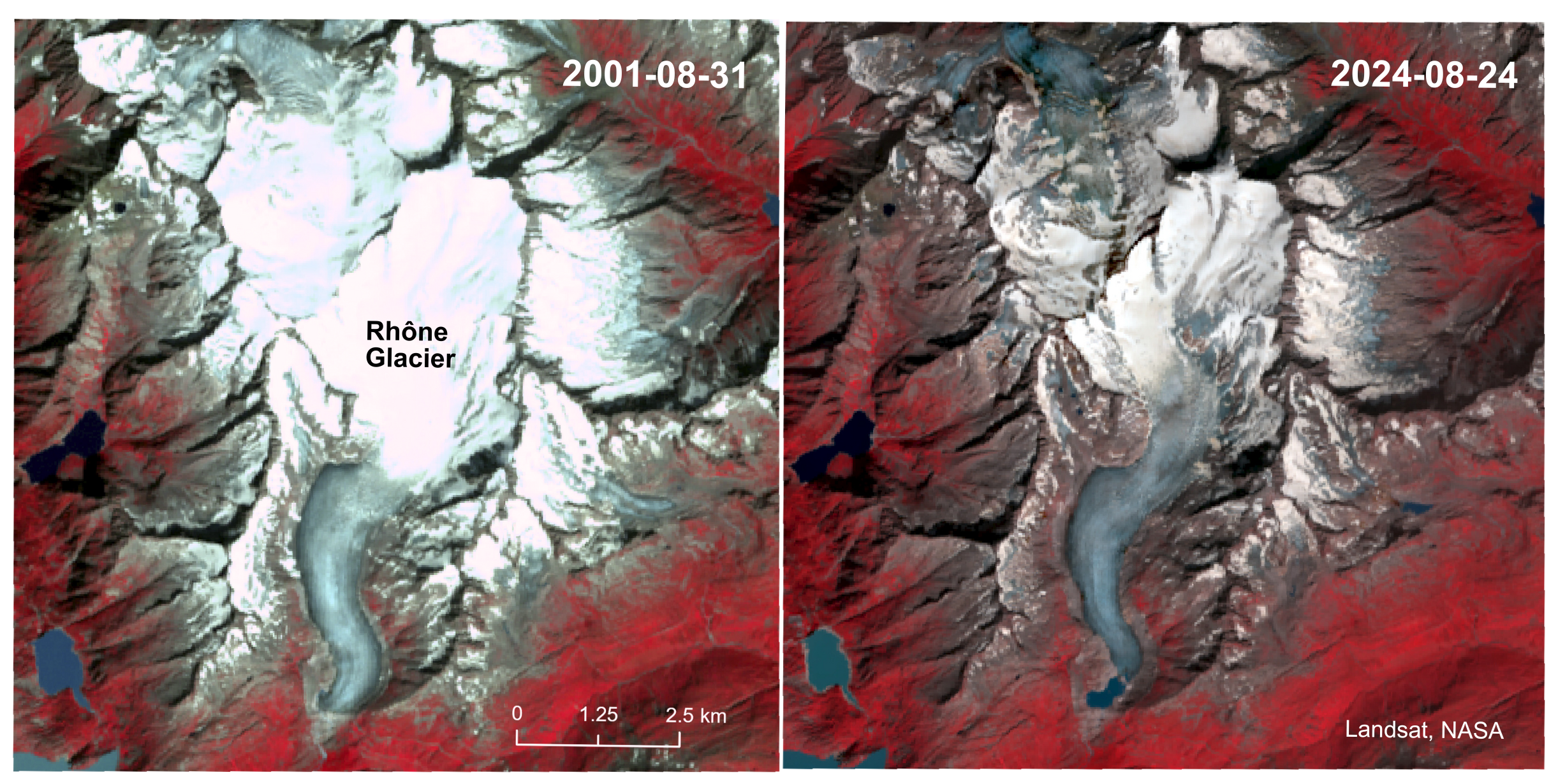

NASA’s Landsat mission, which has been monitoring the Earth since 1972, has provided invaluable data on glacier loss. False-colour Landsat satellite images showcase the heavily visited Rhône Glacier and the source of the Rhône River in Switzerland. The image, comprising infrared, red, and green bands, highlights glaciers in bluish-white tones, while the surrounding vegetation appears red. A comparison of the images taken in August 2001 and August 2024 reveals a striking reduction in the area covered by the glacier.

The Rhône Glacier in Switzerland in August 2001 and August 2024, based on false-colour imagery from the Landsat 7 and 8 satellites.

Satellite data can be used to track changes in the glacial area, analyse shifts in glacier height, and measure volume variations. As glaciers increase in mass, they start to move, and this movement can be monitored using active sensors like IceSAT-2/GLAS and radars such as the Sentinel-1 satellite.

Melting glaciers are altering Europe’s borders

The implications of melting glaciers go beyond ecological concerns – this phenomenon also has geopolitical consequences. Significant sections of the borders between Italy, Switzerland, and Austria are defined by watershed lines that run along the highest mountain ridges.

As glaciers melt or mountain peaks collapse, the established natural boundaries between countries can shift. In 2006, Italy and Austria signed an agreement allowing their shared border to be redrawn in response to shifting mountain ridges. Similarly, the border between Italy and Switzerland has also become subject to adjustment: for instance, in 2024, the melting of the Matterhorn Glacier shifted the mountain’s highest point toward Italy, thereby slightly expanding Switzerland’s territory.

However, changing national borders is not the only issue. The Alps are critical to feeding major river networks such as the Rhône and the Rhine, which run through several countries. In Switzerland, many villages located near glaciers rely on tourism, which is directly tied to this natural phenomenon. While local efforts, such as the use of reflective geotextiles to slow glacial melt, can provide temporary relief, long-term solutions require coordinated global action to combat climate change and mitigate its impact on this vulnerable region.