“Game of Thrones” Lithuanian Style: The Mystery Behind Karigaila’s Murder

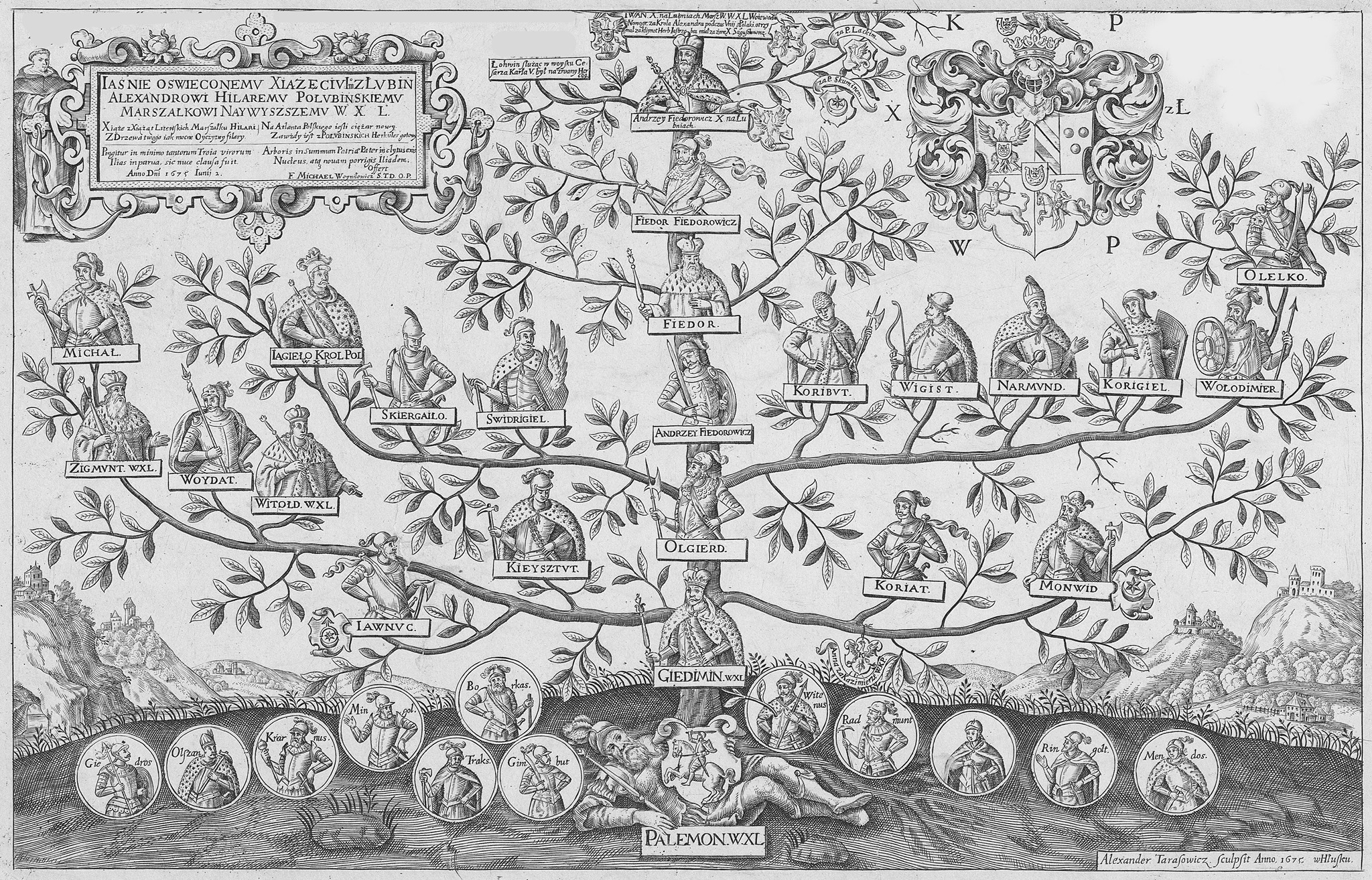

The recent release of Season 2 of “House of the Dragon” has brought us back to the medieval fantasy realm of George Martin’s “Game of Thrones”. Although the series is based on fictional books, the author drew extensively from real medieval history, including the Hundred Years’ War, the Wars of the Roses, and the Crusades. Medieval Lithuania was also not without its share of intriguing moments, one of which was the mysterious death of Karigaila, the brother of Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) and cousin to Vytautas: he was beheaded in 1390 while defending Vilnius Castle against the Crusaders. Dr Antanas Petrilionis, researcher at the Faculty of History of Vilnius University (VU), has tried to unravel the threads of this murderous story dating back over six centuries.

The recent release of Season 2 of “House of the Dragon” has brought us back to the medieval fantasy realm of George Martin’s “Game of Thrones”. Although the series is based on fictional books, the author drew extensively from real medieval history, including the Hundred Years’ War, the Wars of the Roses, and the Crusades. Medieval Lithuania was also not without its share of intriguing moments, one of which was the mysterious death of Karigaila, the brother of Jogaila (Władysław II Jagiełło) and cousin to Vytautas: he was beheaded in 1390 while defending Vilnius Castle against the Crusaders. Dr Antanas Petrilionis, researcher at the Faculty of History of Vilnius University (VU), has tried to unravel the threads of this murderous story dating back over six centuries.

Fatal attack

Dr Petrilionis reveals that the story of Karigaila’s demise resembles a crime thriller – the conflicting yet intertwined accounts of his murder blur the lines of truth: “The ongoing conflict between the cousins – Vytautas and Jogaila, King of Poland – led to Vytautas’ second retreat to the State of the Teutonic Order in early 1390. At that time, the Order was gearing up for a major military campaign. The status and scale of such marches or raids in Lithuania were determined by the presence of prominent Western European delegates. This was also true in 1390. Historical records indicate that many knights, primarily from France and England, started heading to Prussia. Henry Bolingbroke, the then Earl of Derby and future King Henry IV of England, also decided to join the “hunting safari” targeting the pagans, even though they had already been baptised for three years.”

According to the historian, the siege began at the end of August 1390 when the Crusaders and their allies reached Vilnius. At that time, the Vilnius Castle complex consisted of the brick Upper and Lower Castles and the wooden Crooked Castle. The latter was located on the site of the present-day Kalnų Parkas. It was the Crooked Castle that became the target of the Crusaders and their companions, including Vytautas and the future King of England.

“Multiple accounts of the castle siege indicate that Karigaila led the defence of the Crooked Castle. This way, historical sources preserved the legacy of the otherwise little-known son of Algirdas, Grand Duke of Lithuania, through the paradox of his physical death,” says the researcher.

Dr Petrilionis claims that contemporary sources provide similar information: “Karigaila and numerous soldiers perished when the Crooked Castle was set on fire. However, it is very surprising that Johann von Posilge, who gave a rather detailed account of the events in Vilnius at the time, left no record of Karigaila’s death. The question is whether the Crusader chronicler intentionally concealed his demise. Obviously, the death of the ruler’s brother was a setback for the Order and sparked a prolonged propaganda conflict between Poland–Lithuania and the Teutonic Order.”

Different versions of the events

Having traced the events that took place after the storming of the castle and Karigaila’s death, Dr Petrilionis believes that the dispute probably originated from a complaint filed by Jogaila; other sources reveal that the Order was accused of beheading Karigaila, his brother. In response to this complaint, Konrad von Wallenrode, Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, addressed the German knights and subordinates in an open letter of 8 December 1390, setting out his own version of the events that had taken place near Vilnius.

“The Commander sought to assert that the unrecognised Duke was killed amid the chaos of the battle, thus rejecting the charges of his deliberate assassination. It is worth noting that the contemporary chronicles (either depicting or omitting Karigaila’s death) make no mention of the Duke’s execution or the desecration of his remains,” notes the VU historian.

Subsequent Crusader correspondence suggests that the Order’s army and its knights were initially unaware of Karigaila’s death – it was only on the fifth day that some Lithuanian survivors reported his murder. The Crusaders also contended that capturing Karigaila as a prisoner of war would have been more advantageous because, in such case, the Duke could have provided much greater benefits to the Order, being King Jogaila’s brother. His captivity could have been very profitable, both politically and financially. Therefore, Karigaila’s death may indeed have been, as the Order’s Grand Master claimed, caused by a reckless act.

The historian considers the possibility that Karigaila may have surrendered himself and was only later killed for unknown reasons: “Historical evidence shows that, during sieges, the Teutonic Order commanders struggled to strictly control diverse forces under different feudal lords. Although the Code of Chivalry established honourable practices for surrender and redemption from captivity, not all knights adhered to these principles in their treatment of prisoners.”

According to Dr Petrilionis, conflicting accounts surrounding the siege of Vilnius in 1390 and Karigaila’s death open the door to various interpretations.

“Different camps (the Teutonic Order, the English Knights, and Poland-Lithuania) had their own perspectives on the events. The Order’s version portrayed Karigaila’s death as an accident in a military encounter; the Polish and Lithuanian accounts from slightly later sources asserted that Karigaila was deliberately beheaded, while the English Knights had another version that emerged after the fateful attack in 1390. It is evident that all of them selectively highlighted the points supporting their perspective while downplaying other relevant circumstances,” notes the historian.

The same fate as Ned Stark: decapitated and impaled on a spear?

Dr Petrilionis states that 26 years later, in 1416, the story of Karigaila’s demise was revived at the Council of Constance amidst the disputes between Poland-Lithuania and the Teutonic Order.

“Among other reproaches, the events of 1390 at Vilnius Castle were also recalled. Jogaila’s complaint against the Order helped reconstruct the course of the siege and revealed various new details. It depicted the murder of Karigaila in graphic detail and, for the first time, mentioned the spearing of the Duke’s severed head and the indecent treatment of his remains. The epithets used to describe Karigaila are truly remarkable: he was marked out as the most Christian and just ruler (princeps christianissimus; princeps iustissimus), and his death was linked to the biblical story of Cain and Abel. The murder of the Christian King’s brother was to be another motive to undermine the Order’s reputation among Western European monarchs.

In response to the written complaint from the Polish side, the Teutonic Order also emphasised Vytautas’ involvement in the campaign. According to them, Vytautas could swear, as could the nobles of England, that the King’s brother had fallen unrecognised along with other defenders. This reasoning should have put Vytautas in a challenging position, with his response potentially resulting in either the rejection or validation of the Polish claim. It is worth noting that as the King of Poland, Jogaila was not at liberty to make unfounded accusations; he had to be assured of their veracity, as he had witnessed his brother’s body being buried in Vilnius Cathedral,” Dr Petrilionis reflects on the circumstances of Karigaila’s death.

The VU researcher characterises the dispute of the Council of Constance as a spectacle marked by relentless accusations from both sides. In its reply, the Order firmly refuted the allegation of spearing the Duke, recalling that after the Battle of Grunwald, Vytautas himself had ordered the beheading of three imprisoned Teutonic brothers.

The English remembers

The lecturer of the VU Faculty of History points out that while the Teutonic Knights were arguing with the representatives of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland about the circumstances of the event, one of the participants in the 1390 campaign – the Earl of Derby, who became King Henry IV of England in 1399 – provided some more resources for English chroniclers.

“His written materials echo the events of 1390, mentioning Skirgaila and Vytautas, as well as the Polish King’s brother who was killed in Vilnius. However, as Karigaila was not mentioned by name, it suggests the fallen Duke’s insignificance in the eyes of the English chronicler. The Polish version presented at the Council of Constance seems to have been unknown or irrelevant to the author, as one chronicler portrays Karigaila as a fierce adversary of Christianity. No doubt, this image of Jogaila’s brother served to justify Henry’s march on Lithuania. Due to Henry’s crusade against the pagans, the author portrayed his military campaign as a battle with the enemies of Christianity.

Another English work, “Historia Anglicana”, gives a broader account of the campaign – it starts with the victory over Skirgaila and mentions the captured dukes. However, this source reiterates the same details concerning Jogaila’s brother, with the addition of the epithet of a slain adversary of Christianity. The narrative includes the noteworthy detail that Henry successfully baptised eight Lithuanians before departing from Vilnius. Interestingly, Henry’s travel account book records a person named Henrico Lettowe: he may have been one of the baptised prisoners, symbolically named in honour of his godfather,” suggests the historian.

According to him, the English chronicles offer a different perspective on the events at Vilnius Castle compared to those of the Council of Constance. The English authors focused on celebrating their countrymen’s march and the pilgrimage mission, including the baptism of Lithuanian captives, providing only fragmentary information on Karigaila’s death.

Was Vytautas behind the brutal assassination?

Maciej Stryjkowski’s “Chronicle” (1582) offers a unique interpretation of Karigaila’s passing and the events of 1390. In this chronicle, Vytautas emerges as the true culprit behind the Duke’s death, not the Teutonic Order or its leaders. Summoned at his cousin’s command, Karigaila was beheaded and impaled on a spear. Vytautas’ involvement not only reverses the previous accounts but also denies the Order’s involvement. “Determining the factors behind Stryjkowski’s version is a challenging task. Vytautas’ participation in the events of 1390 was well-known and established by Jan Długosz. Perhaps it was the desire always to see Vytautas’ influential role (both positive and negative) that dictated such an assessment of the events,” reflects the historian.

He notes that the portrayal of Vytautas as the primary instigator of Karigaila’s death was developed nearly a century later by historian Albert Wijuk Kojałowicz, who also added a more dramatic dimension.

“However, Kojałowicz’s interpretation includes a subjective evaluation of the events: “Here, in front of his cousin, he lost his life... Vytautas ordered his execution by beheading and displaying the head on a spear around the camp: pitiful proof that sibling rivalries are always incredibly fierce”.” In the eyes of Kojałowicz, Karigaila became the victim of Vytautas’ anger and brutality. The motif of Karigaila’s death in the works of Stryjkowski and Kojałowicz is closely linked to the general assessment of Vytautas. On the one hand, he used to be portrayed as a hero, and on the other, as a strong and sometimes even tyrannical ruler guided by the internal logic of the historical narrative, i.e. directed his actions and ambition to reclaim his father’s land. In this Lithuanian tradition, Karigaila is a tragic yet minor figure in the grand narrative of Vytautas”, explains Dr Petrilionis.

According to the medievalist, Karigaila’s demise sparked a decades-long dispute between the Teutonic Order and Poland-Lithuania, with both sides trying to prove their right. The Poles and Lithuanians denounced the inappropriate and cruel treatment of the nobleman of the Algirdas family (Algirdaičiai), while the Order sought to dispel such accusations.

“Whatever the truth, although relatively obscure, the story of Karigaila has endured in historical memory. His death unveils the harsh reality, cruelty, political games, and intrigues of medieval life – no less gripping than “Game of Thrones” or the current “House of the Dragon” series,” concludes Dr Petrilionis.